On the Future

VOL 3 ISSUE 3

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

8 August 2019

The editorial board is pleased to share with new and returning readers issue 3.3 of Process, On the Future. We received an especially broad range of submissions for this issue, and it we were impressed by the richness of undergraduate thinking on the future. Submissions considered literary and historical imaginings of the future; scientific and political engagements with the future; and social and cultural visions of alternative futures.

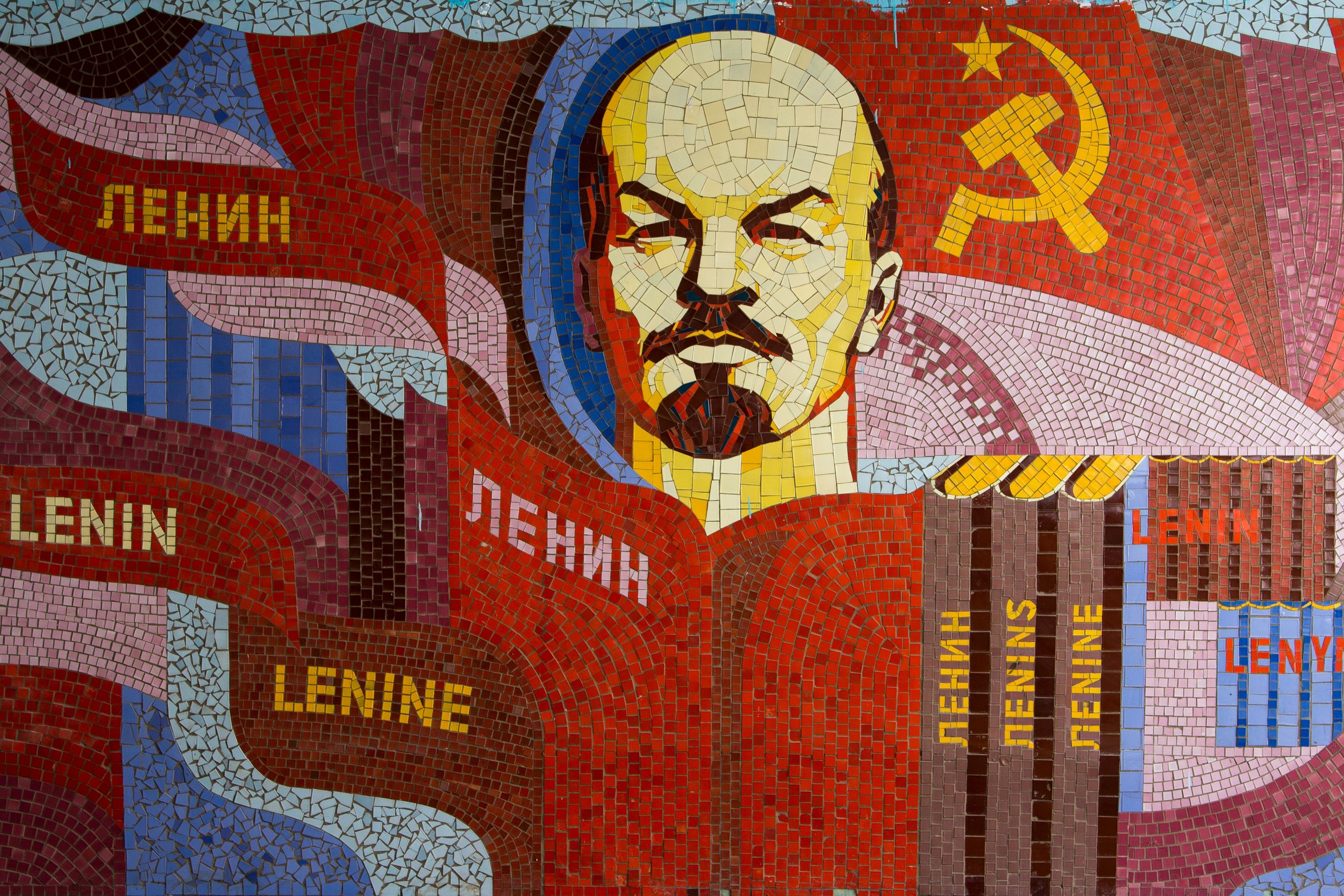

Kasia Majewski’s essay, “Communizing Memory: Controlling the Past, Present, and Future in the ČSSR,” demonstrates how state communism sought to manipulate cultural memory and how the Czech public resisted these official manipulations of history. Analyzing competing forces in public memory-making, Majewski points to a generative gap between state narratives and public memory. Studying how power operates in the construction of memory gives us a sense, Majewski claims, of who will make decisions about the future. Zoe Bracken’s “In Defense of Utopia” also thinks about how power operates in public narratives. Who gets to imagine the future, and what are the stakes of this? Arguing that utopic thinking is not only wise, but necessary, Bracken engages queer theory and aesthetic theory to draw out the emancipatory utopianism of Janelle Monae’s Dirty Computer. Following, like Bracken, the possibilities for justice in alternative visions of space and movement, Minh Vu considers what an erotic gaze, as opposed to a pornopraphic gaze, might make possible. Vu synthesizes work in feminsm, queer theory, and ethnography to imagine different relations between people and alternative understandings of self.

All three essays make clear that our sense of the future is bound up with our thinking about the past and present. Our uses of history--hegemonic understandings of the past, or possibilities of seeing history in a new way--help determine what the present feels like and what visions of the future are possible. Similarly, practicing seeing the future in a way other than as an extension of the present can shift the present and help us re-see the past. We hope these pieces inspire further discussion, reflections, and thinking about the future. We also invite readers to read the call for papers for our next issue, On Failure, and we look forward to receiving your submissions!

Sincerely,

Kathleen Reeves & Emily George

Editors-in-Chief

COMMUNIZING MEMORY:

Controlling the Past, Present, and Future in the ČSSR

Kasia Majewski

Majewski’s research interrogates the role that historical memory plays in the politics of cultural control using Czechoslovakia under communism as the site of study. She argues that the Czech government’s decision to either appropriate or erase certain historical narratives was an attempt to legitimize often-oppressive policies and state actions. Exploring the transition into a communist economic, political and cultural system, Majewski shows how the transitions between past and present will shape the future of rebuilding and reclaiming a Czech national identity for the future.

In Defense of the Future

Zoë Bracken

Who has the power and position to imagine the future? Do traditional modes of Utopian thinking make room for marginalized subjects? What are the emancipatory potentials of Utopianism in art? Bracken’s critique of Janelle Monáe’s recent “emotion picture” Dirty Computer (2018) seeks to answer these questions. Combining sociological thought, queer theory, and aesthetic critique she argues that Utopia exists at the center of all levels of radical, imaginative, and futuristic consciousness. This essay is comprised of excerpts from Bracken’s undergraduate thesis in sociology at Vassar College.

Gazing at the Gaze: To De-pornographize and Re-eroticize

Minh Vu

Vu’s work combines studies on the gaze with spatiality theory to reassess the function and theories of pornography for the future. They argue for a turn away from the much-studied pornographic gaze opening up new spaces and avenues of interrogation to explore the erotic gaze. The roots of this project emerge from Audre Lorde’s concept of the “erotic principle”, and bell hook’s “oppositional gaze”, serving as the foundation for Vu’s treatment of the erotic gaze as a site of resistance against oppression.