BLK is Back

Travis York

Travis York (he/they) is a current MA student in Women and Gender Studies at the University of Toronto. Travis graduated in 2023 from Princeton University with a degree in History. Travis’s research explores the intersections of disability, gender, and sexuality within the late twentieth-century United States. They are especially interested in the history of social movements and representations of social justice work in print media, which often highlight the public-facing structures of social justice organizations. Their work highlights the lasting impacts of various historical social justice organizations within the United States.

Abstract

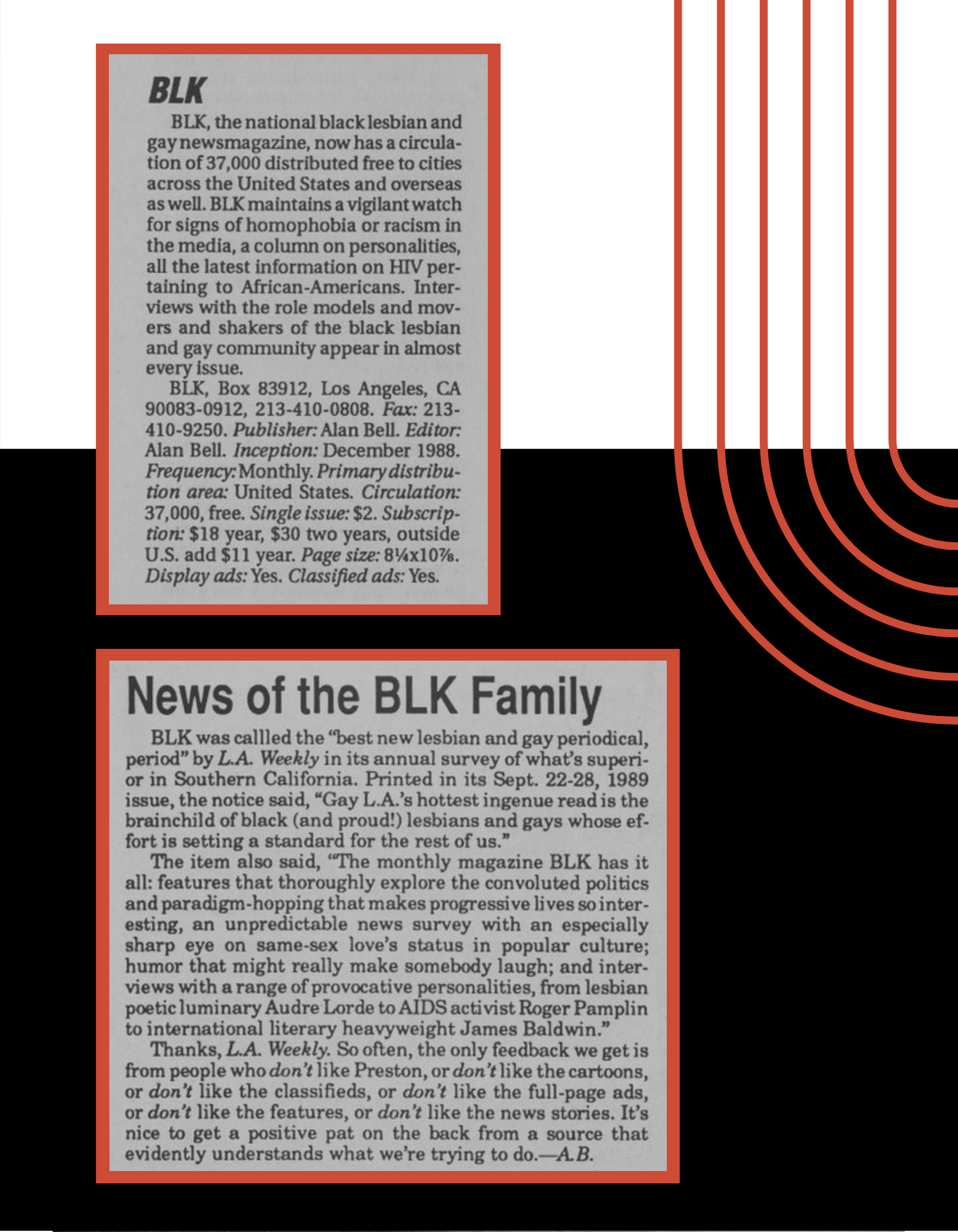

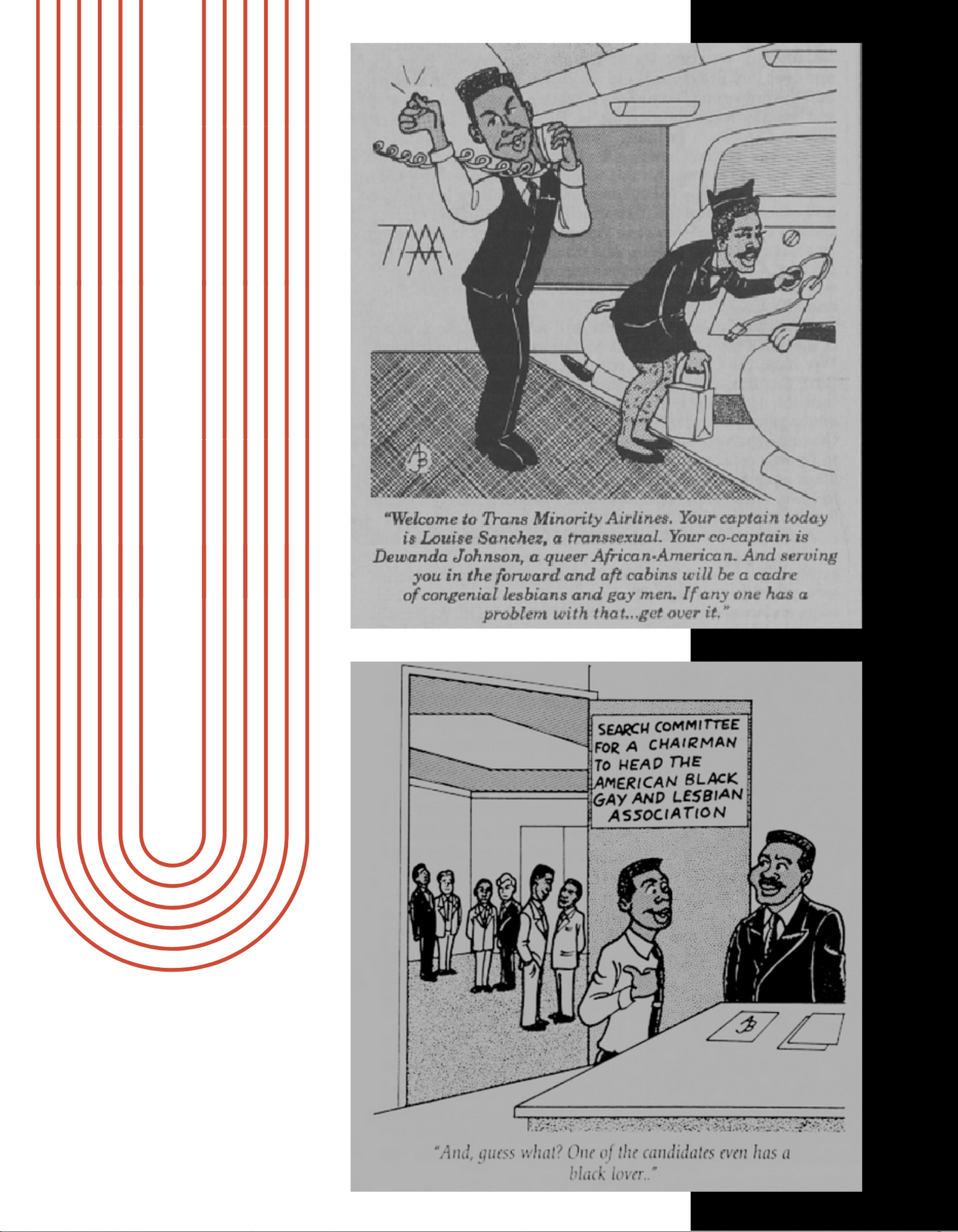

In 1999, Cathy Cohen critically documented the variety of responses, and lack thereof, to AIDS in American society in her book, The Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS and the Breakdown of Black Politics. Notably, she recounts a lack of adept responses from popular Black newspapers to the AIDS crisis. This project picks up Cohen’s work to dive deeper into Black communities’ responses to the AIDS crisis to show that, while most popular news outlets lacked a vigorous response to AIDS, there were responses from select communities. This project centers on BLK magazine, which was published from December 1988 to March 1994. BLK magazine, which was published in Los Angeles, California, was one of the few news sources that actively covered the AIDS epidemic. By October 1991, slightly under three years after the magazine began circulation, BLK had already published 207 articles relating to HIV and AIDS while also continually publishing monthly reports from the CDC. Dedicated to the issues facing Black gay and lesbian communities, BLK routinely covered stories on the AIDS epidemic. BLK was a popular magazine among Black gay and lesbian communities, with a circulation of 37,000 copies. From reporting on AIDS to advertisements aimed at the prevention and a better livelihood of those contracting AIDS to comics providing joy and an ability to critique society, BLK showcases an active response to AIDS within Black queer communities. The “Making Headlines” section documents various news articles published in BLK that highlight the combined impact of racism and homophobia on Black queer communities, especially in light of the AIDS epidemic. In “Screwing Support,” various AIDS prevention advertisements are shown as they appeared in BLK. This section also includes an important line from Audre Lorde on the need for Black men and women to unite in their efforts. The final section, “Comic Relief,” highlights several comics from BLK to simultaneously show that these communities could laugh amid a crisis and show the social critique available within comics. Comics allowed for a space to humorously critique society. In viewing BLK as one news source that actively covered the AIDS crisis and the most pressing issues facing Black queer communities, it can be seen that some sources paid attention the AIDS crisis. Cohen’s argument that many major news sources ignored the AIDS epidemic or covered it poorly still stands. However, it is important to realize that her study is not to be applied to all news sources. These sources are critical to understanding how the AIDS epidemic was perceived by Black- and queer-centered media. In sharing the words of BLK, there is a remembrance of all those stories still left untold. The AIDS epidemic is not just a singular history, it is lived realities of dark memories. Yet, even in the midst of this darkness, there is hope, joy, friendship, love, and even some laughter.